14. Advanced Zope Scripting¶

In the chapter entitled “Basic Zope Scripting”, you have seen how to manage Zope objects programmatically. In this chapter, we will explore this topic some more. Subjects discussed include additional scripting objects, script security, and calling script objects from presentation objects like Page Templates. As we have mentioned before, separation of logic and presentation is a key factor in implementing maintainable web applications.

What is logic and how does it differ from presentation? Logic provides those actions which change objects, send messages, test conditions and respond to events, whereas presentation formats and displays information and reports. Typically you will use Page Templates to handle presentation, and Zope scripting to handle logic.

14.1. Warning¶

Zope Script objects are objects that encapsulate a small chunk of code written in a programming language. They first appeared in Zope 2.3, and have been the preferred way to write programming logic in Zope for many years. Today it is discouraged to use Scripts for any but the most minimal logic. If you want to create more than trivial logic, you should approach this by creating a Python package and write your logic on the file system.

This book does not cover this development approach in its details. This chapter is still useful to read, as it allows you to get an understanding on some of the more advanced techniques and features of Zope.

14.2. Calling Scripts¶

In the “Basic Zope Scripting” chapter, you learned how to call scripts from the web and, conversely, how to call Page Templates from Python-based Scripts. In fact scripts can call scripts which call other scripts, and so on.

14.2.1. Calling Scripts from Other Objects¶

You can call scripts from other objects, whether they are Page Templates or Scripts (Python). The semantics of each language differ slightly, but the same rules of acquisition apply. You do not necessarily have to know what language is used in the script you are calling; you only need to pass it any parameters that it requires, if any.

14.2.1.1. Calling Scripts from Page Templates¶

Calling scripts from Page Templates is much like calling them by URL or from Python. Just use standard TALES path expressions as described in the chapter entitled Using Zope Page Templates For example:

<div tal:replace="context/hippo/feed">

Output of feed()

</div>

The inserted value will be HTML-quoted. You can disable quoting by using the structure keyword, as described in the chapter entitled Advanced Page Templates

To call a script without inserting a value in the page, you can use define and ignore the variable assigned:

<div tal:define="dummy context/hippo/feed" />

In a page template, context refers to the current context. It behaves much like the context variable in a Python-based Script. In other words, hippo and feed will both be looked up by acquisition.

If the script you call requires arguments, you must use a TALES python expression in your template, like so:

<div tal:replace="python:context.hippo.feed(food='spam')">

Output of feed(food='spam')

</div>

Just as in Path Expressions, the ‘context’ variable refers to the acquisition context the Page Template is called in.

The python expression above is exactly like a line of code you might write in a Script (Python).

One difference is the notation used for attribute access – Script (Python) uses the standard Python period notation, whereas in a TALES path expression, a forward slash is used.

For further reading on using Scripts in Page Templates, refer to the chapter entitled Advanced Page Templates.

14.2.1.2. Calling scripts from Python¶

Calling scripts from other scripts works similar to calling scripts from page templates, except that you must always use explicit calling (by using parentheses). For example, here is how you might call the updateInfo script from Python:

new_color='brown'

context.updateInfo(color=new_color,

pattern="spotted")

Note the use of the context variable to tell Zope to find updateInfo by acquisition.

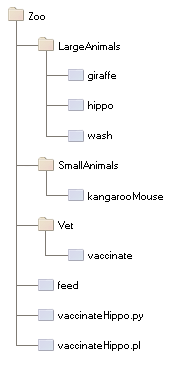

Zope locates the scripts you call by using acquisition the same way it does when calling scripts from the web. Returning to our hippo feeding example of the last section, let’s see how to vaccinate a hippo from Python. The figure below shows a slightly updated object hierarchy that contains a script named vaccinateHippo.py.

A collection of objects and scripts

Here is how you can call the vaccinate script on the hippo obect from the vaccinateHippo.py script:

context.Vet.LargeAnimals.hippo.vaccinate()

In other words, you simply access the object by using the same acquisition path as you would use if you called it from the web. The result is the same as if you visited the URL Zoo/Vet/LargeAnimals/hippo/vaccinate. Note that in this Python example, we do not bother to specify Zoo before Vet. We can leave Zoo out because all of the objects involved, including the script, are in the Zoo folder, so it is implicitly part of the acquisition chain.

14.2.1.3. Calling Scripts: Summary and Comparison¶

Let’s recap the ways to call a hypothetical updateInfo script on a foo object, with argument passing: from your web browser, from Python and from Page Templates.

by URL:

http://my-zope-server.com:8080/foo/updateInfo?amount=lots

from a Script (Python):

context.foo.updateInfo(amount="lots")

from a Page Template:

<span tal:content="context/foo/updateInfo" />

from a Page Template, with arguments:

<span tal:content="python:context.foo.updateInfo(amount='lots')" />

Regardless of the language used, this is a very common idiom to find an object, be it a script or any other kind of object: you ask the context for it, and if it exists in this context or can be acquired from it, it will be used.

Zope will throw a KeyError exception if the script you are calling cannot be acquired. If you are not certain that a given script exists in the current context, or if you want to compute the script name at run-time, you can use this Python idiom:

updateInfo = getattr(context, "updateInfo", None)

if updateInfo is not None:

updateInfo(color="brown", pattern="spotted")

else:

# complain about missing script

return "error: updateInfo() not found"

The getattr function is a Python built-in. The first argument specifies an object, the second an attribute name. The getattr function will return the named attribute, or the third argument if the attribute cannot be found. So in the next statement we just have to test whether the updateInfo variable is None, and if not, we know we can call it.

14.3. Using External Methods¶

Sometimes the security constraints imposed by Python-based Scripts, DTML and ZPT get in your way. For example, you might want to read files from disk, or access the network, or use some advanced libraries for things like regular expressions or image processing. In these cases you can use External Methods. We encountered External Methods briefly in the chapter entitled Using Basic Zope Objects . Now we will explore them in more detail.

To create and edit External Methods you need access to the filesystem. This makes editing these scripts more cumbersome since you can’t edit them right in your web browser. However, requiring access to the server’s filesystem provides an important security control. If a user has access to a server’s filesystem they already have the ability to harm Zope. So by requiring that unrestricted scripts be edited on the filesystem, Zope ensures that only people who are already trusted have access.

External Method code is created and edited in files on the Zope server in the Extensions directory. This directory is located in the top-level Zope directory. Alternately you can create and edit your External Methods in an Extensions directory inside an installed Zope product directory, or in your INSTANCE_HOME directory if you have one. See the chapter entitled “Installing and Starting Zope”:InstallingZope.html>`_ for more about INSTANCE_HOME.

Let’s take an example. Create a file named example.py in the Zope Extensions directory on your server. In the file, enter the following code:

def hello(name="World"):

return "Hello %s." % name

You’ve created a Python function in a Python module. But you have not yet created an External Method from it. To do so, we must add an External Method object in Zope.

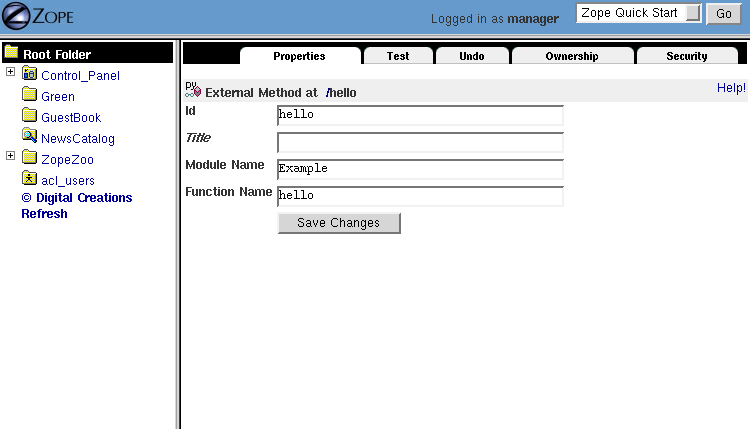

To add an External Method, choose External Method from the product add list. You will be taken to a form where you must provide an id. Type “hello” into the Id field, type “hello” in the Function name field, and type “example” in the Module name field. Then click the Add button. You should now see a new External Method object in your folder. Click on it. You should be taken to the Properties view of your new External Method as shown in the figure below.

External Method Properties view

Note that if you wish to create several related External Methods, you do not need to create multiple modules on the filesystem. You can define any number of functions in one module, and add an External Method to Zope for each function. For each of these External Methods, the module name would be the same, but function name would vary.

Now test your new script by going to the Test view. You should see a greeting. You can pass different names to the script by specifying them in the URL. For example, ‘hello?name=Spanish+Inquisition’.

This example is exactly the same as the “hello world” example that you saw for Python-based scripts. In fact, for simple string processing tasks like this, scripts offer a better solution since they are easier to work with.

The main reasons to use an External Method are to access the filesystem or network, or to use Python packages that are not available to restricted scripts.

For example, a Script (Python) cannot access environment variables on the host system. One could access them using an External Method, like so:

def instance_home():

import os

return os.environ.get('INSTANCE_HOME')

Regular expressions are another useful tool that are restricted from Scripts. Let’s look at an example. Assume we want to get the body of an HTML Page (everything between the ‘body’ and ‘/body’ tags):

import re

pattern = r"<\s*body.*?>(.*?)</body>"

regexp = re.compile(pattern, re.IGNORECASE + re.DOTALL)

def extract_body(htmlstring):

"""

If htmlstring is a complete HTML page, return the string

between (the first) <body> ... </body> tags

"""

matched = regexp.search(htmlpage)

if matched is None: return "No match found"

body = matched.group(1)

return body

Note that we import the ‘re’ module and define the regular expression at the module level, instead of in the function itself; the ‘extract_body()’ function will find it anyway. Thus, the regular expression is compiled once, when Zope first loads the External Method, rather than every time this External Method is called. This is a common optimization tactic.

Now put this code in a module called ‘my_extensions.py’. Add an ‘External Method’ with an id of ‘body_external_m’; specify ‘my_extensions’ for the ‘Module Name’ to use and, ‘extract_body’ for ‘Function Name’.

You could call this for example in a ‘Script (Python)’ called ‘store_html’ like this:

## Script (Python) "store_html"

##

# code to get 'htmlpage' goes here...

htmlpage = "some string, perhaps from an uploaded file"

# now extract the body

body = context.body_external_m(htmlpage)

# now do something with 'body' ...

... assuming that body_external_m can be acquired by store_html. This is obviously not a complete example; you would want to get a real HTML page instead of a hardcoded one, and you would do something sensible with the value returned by your External Method.

14.3.1. Creating Thumbnails from Images¶

Here is an example External Method that uses the Python Imaging Library (PIL) to create a thumbnail version of an existing Image object in a Folder. Enter the following code in a file named Thumbnail.py in the Extensions directory:

def makeThumbnail(self, original_id, size=200):

"""

Makes a thumbnail image given an image Id when called on a Zope

folder.

The thumbnail is a Zope image object that is a small JPG

representation of the original image. The thumbnail has an

'original_id' property set to the id of the full size image

object.

"""

import PIL

from StringIO import StringIO

import os.path

# none of the above imports would be allowed in Script (Python)!

# Note that PIL.Image objects expect to get and save data

# from the filesystem; so do Zope Images. We can get around

# this and do everything in memory by using StringIO.

# Get the original image data in memory.

original_image=getattr(self, original_id)

original_file=StringIO(str(original_image.data))

# create the thumbnail data in a new PIL Image.

image=PIL.Image.open(original_file)

image=image.convert('RGB')

image.thumbnail((size,size))

# get the thumbnail data in memory.

thumbnail_file=StringIO()

image.save(thumbnail_file, "JPEG")

thumbnail_file.seek(0)

# create an id for the thumbnail

path, ext=os.path.splitext(original_id)

thumbnail_id=path + '.thumb.jpg'

# if there's an old thumbnail, delete it

if thumbnail_id in self.objectIds():

self.manage_delObjects([thumbnail_id])

# create the Zope image object for the new thumbnail

self.manage_addProduct['OFSP'].manage_addImage(thumbnail_id,

thumbnail_file,

'thumbnail image')

# now find the new zope object so we can modify

# its properties.

thumbnail_image=getattr(self, thumbnail_id)

thumbnail_image.manage_addProperty('original_id', original_id, 'string')

Notice that the first parameter to the above function is called self. This parameter is optional. If self is the first parameter to an External Method function definition, it will be assigned the value of the calling context (in this case, a folder). It can be used much like the context we have seen in Scripts (Python).

You must have PIL installed for this example to work. Installing PIL is beyond the scope of this book, but note that it is important to choose a version of PIL that is compatible with the version of Python that is used by your version of Zope. See the “PythonWorks website”:http://www.pythonware.com/products/pil/index.htm for more information on PIL.

To continue our example, create an External Method named makeThumbnail that uses the makeThumbnail function in the Thumbnail module.

Now you have a method that will create a thumbnail image. You can call it on a Folder with a URL like ImageFolder/makeThumbnail?original_id=Horse.gif This would create a thumbnail image named ‘Horse.thumb.jpg’.

You can use a script to loop through all the images in a folder and create thumbnail images for them. Create a Script (Python) named makeThumbnails:

## Script (Python) "makeThumbnails"

##

for image_id in context.objectIds('Image'):

context.makeThumbnail(image_id)

This will loop through all the images in a folder and create a thumbnail for each one.

Now call this script on a folder with images in it. It will create a thumbnail image for each contained image. Try calling the makeThumbnails script on the folder again and you’ll notice it created thumbnails of your thumbnails. This is no good. You need to change the makeThumbnails script to recognize existing thumbnail images and not make thumbnails of them. Since all thumbnail images have an original_id property you can check for that property as a way of distinguishing between thumbnails and normal images:

## Script (Python) "makeThumbnails"

##

for image in context.objectValues('Image'):

if not image.hasProperty('original_id'):

context.makeThumbnail(image.getId())

Delete all the thumbnail images in your folder and try calling your updated makeThumbnails script on the folder. It seems to work correctly now.

Now with a little DTML you can glue your script and External Method together. Create a DTML Method called displayThumbnails:

<dtml-var standard_html_header>

<dtml-if updateThumbnails>

<dtml-call makeThumbnails>

</dtml-if>

<h2>Thumbnails</h2>

<table><tr valign="top">

<dtml-in expr="objectValues('Image')">

<dtml-if original_id>

<td>

<a href="&dtml-original_id;"><dtml-var sequence-item></a>

<br />

<dtml-var original_id>

</td>

</dtml-if>

</dtml-in>

</tr></table>

<form>

<input type="submit" name="updateThumbnails"

value="Update Thumbnails" />

</form>

<dtml-var standard_html_footer>

When you call this DTML Method on a folder it will loop through all the images in the folder and display all the thumbnail images and link them to the originals as shown in the figure below.

Displaying thumbnail images

This DTML Method also includes a form that allows you to update the thumbnail images. If you add, delete or change the images in your folder you can use this form to update your thumbnails.

This example shows a good way to use scripts, External Methods and DTML together. Python takes care of the logic while the DTML handles presentation. Your External Methods handle external packages such as PIL while your scripts do simple processing of Zope objects. Note that you could just as easily use a Page Template instead of DTML.

14.3.2. Processing XML with External Methods¶

You can use External Methods to do nearly anything. One interesting thing that you can do is to communicate using XML. You can generate and process XML with External Methods.

Zope already understands some kinds of XML messages such as XML-RPC and WebDAV. As you create web applications that communicate with other systems you may want to have the ability to receive XML messages. You can receive XML a number of ways: you can read XML files from the file system or over the network, or you can define scripts that take XML arguments which can be called by remote systems.

Once you have received an XML message you must process the XML to find out what it means and how to act on it. Let’s take a quick look at how you might parse XML manually using Python. Suppose you want to connect your web application to a “Jabber”:http://www.jabber.com/ chat server. You might want to allow users to message you and receive dynamic responses based on the status of your web application. For example suppose you want to allow users to check the status of animals using instant messaging. Your application should respond to XML instant messages like this:

<message to="cage_monitor@zopezoo.org" from="user@host.com">

<body>monkey food status</body>

</message>

You could scan the body of the message for commands, call a script and return responses like this:

<message to="user@host.com" from="cage_monitor@zopezoo.org">

<body>Monkeys were last fed at 3:15</body>

</message>

Here is a sketch of how you could implement this XML messaging facility in your web application using an External Method:

# Uses Python 2.x standard xml processing packages. See

# http://www.python.org/doc/current/lib/module-xml.sax.html for

# information about Python's SAX (Simple API for XML) support If

# you are using Python 1.5.2 you can get the PyXML package. See

# http://pyxml.sourceforge.net for more information about PyXML.

from xml.sax import parseString

from xml.sax.handler import ContentHandler

class MessageHandler(ContentHandler):

"""

SAX message handler class

Extracts a message's to, from, and body

"""

inbody=0

body=""

def startElement(self, name, attrs):

if name=="message":

self.recipient=attrs['to']

self.sender=attrs['from']

elif name=="body":

self.inbody=1

def endElement(self, name):

if name=="body":

self.inbody=0

def characters(self, content):

if self.inbody:

self.body=self.body + content

def receiveMessage(self, message):

"""

Called by a Jabber server

"""

handler=MessageHandler()

parseString(message, handler)

# call a script that returns a response string

# given a message body string

response_body=self.getResponse(handler.body)

# create a response XML message

response_message="""

<message to="%s" from="%s">

<body>%s</body>

</message>""" % (handler.sender, handler.recipient, response_body)

# return it to the server

return response_message

The receiveMessage External Method uses Python’s SAX (Simple API for XML) package to parse the XML message. The MessageHandler class receives callbacks as Python parses the message. The handler saves information its interested in. The External Method uses the handler class by creating an instance of it, and passing it to the parseString function. It then figures out a response message by calling getResponse with the message body. The getResponse script (which is not shown here) presumably scans the body for commands, queries the web applications state and returns some response. The receiveMessage method then creates an XML message using response and the sender information and returns it.

The remote server would use this External Method by calling the receiveMessage method using the standard HTTP POST command. Voila, you’ve implemented a custom XML chat server that runs over HTTP.

14.3.3. External Method Gotchas¶

While you are essentially unrestricted in what you can do in an External Method, there are still some things that are hard to do.

While your Python code can do as it pleases if you want to work with the Zope framework you need to respect its rules. While programming with the Zope framework is too advanced a topic to cover here, there are a few things that you should be aware of.

Problems can occur if you hand instances of your own classes to Zope and expect them to work like Zope objects. For example, you cannot define a class in your External Method and assign an instance of this class as an attribute of a Zope object. This causes problems with Zope’s persistence machinery. If you need to create new kinds of persistent objects, it’s time to learn about writing Zope Products. Writing a Product is beyond the scope of this book. You can learn more by reading the “Zope Developers’ Guide”:http://www.zope.org/Documentation/Books/ZDG/current

14.4. Advanced Acquisition¶

In the chapter entitled Acquisition , we introduced acquisition by containment, which we have been using throughout this chapter. In acquisition by containment, Zope looks for an object by going back up the containment hierarchy until it finds an object with the right id. In Chapter 7 we also mentioned context acquisition, and warned that it is a tricky subject capable of causing your brain to explode. If you are ready for exploding brains, read on.

The most important thing for you to understand in this chapter is that context acquisition exists and can interfere with whatever you are doing. Today it is seen as a fragile and complex topic and rarely ever used in practice.

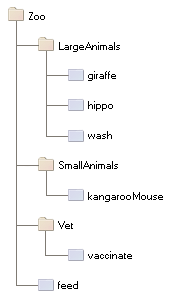

Recall our Zoo example introduced earlier in this chapter.

Zope Zoo Example hierarchy

We have seen how Zope uses URL traversal and acquisition to find objects in higher containers. More complex arrangements are possible. Suppose you want to call the vaccinate script on the hippo object. What URL can you use? If you visit the URL Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/vaccinate Zope will not be able to find the vaccinate script since it isn’t in any of the hippo object’s containers.

The solution is to give the path to the script as part of the URL. Zope allows you to combine two or more URLs into one in order to provide more acquisition context! By using acquisition, Zope will find the script as it backtracks along the URL. The URL to vaccinate the hippo is Zoo/Vet/LargeAnimals/hippo/vaccinate. Likewise, if you want to call the vaccinate script on the kargarooMouse object you should use the URL Zoo/Vet/SmallAnimals/kargarooMouse/vaccinate.

Let’s follow along as Zope traverses the URL Zoo/Vet/LargeAnimals/hippo/vaccinate. Zope starts in the root folder and looks for an object named Zoo. It moves to the Zoo folder and looks for an object named Vet. It moves to the Vet folder and looks for an object named LargeAnimals. The Vet folder does not contain an object with that name, but it can acquire the LargeAnimals folder from its container, Zoo folder. So it moves to the LargeAnimals folder and looks for an object named hippo. It then moves to the hippo object and looks for an object named vaccinate. Since the hippo object does not contain a vaccinate object and neither do any of its containers, Zope backtracks along the URL path trying to find a vaccinate object. First it backs up to the LargeAnimals folder where vaccinate still cannot be found. Then it backs up to the Vet folder. Here it finds a vaccinate script in the Vet folder. Since Zope has now come to the end of the URL, it calls the vaccinate script in the context of the hippo object.

Note that we could also have organized the URL a bit differently. Zoo/LargeAnimals/Vet/hippo/vaccinate would also work. The difference is the order in which the context elements are searched. In this example, we only need to get vaccinate from Vet, so all that matters is that Vet appears in the URL after Zoo and before hippo.

When Zope looks for a sub-object during URL traversal, it first looks for the sub-object in the current object. If it cannot find it in the current object it looks in the current object’s containers. If it still cannot find the sub-object, it backs up along the URL path and searches again. It continues this process until it either finds the object or raises an error if it cannot be found. If several context folders are used in the URL, they will be searched in order from left to right.

Context acquisition can be a very useful mechanism, and it allows you to be quite expressive when you compose URLs. The path you tell Zope to take on its way to an object will determine how it uses acquisition to look up the object’s scripts.

Note that not all scripts will behave differently depending on the traversed URL. For example, you might want your script to acquire names only from its parent containers and not from the URL context. To do so, simply use the container variable instead of the context variable in the script, as described above in the section “Using Python-based Scripts.”

14.4.1. Context Acquisition Gotchas¶

14.4.1.1. Containment before context¶

It is important to realize that context acquisition supplements container acquisition. It does not override container acquisition.

14.4.1.2. One at a time¶

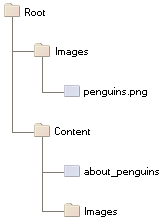

Another point that often confuses new users is that each element of a path “sticks” for the duration of the traversal, once it is found. Think of it this way: objects are looked up one at a time, and once an object is found, it will not be looked up again. For example, imagine this folder structure:

Acquisition example folder structure

Now suppose that the about_penguins page contains a link to Images/penguins.png. Shouldn’t this work? Won’t /Images/penguins.png succeed when /Content/Images/penguins.png fails? The answer is no. We always traverse from left to right, one item at a time. First we find Content, then Images within it; penguins.png appears in neither of those, and we haved searched all parent containers of every element in the URL, so there is nothing more to search in this URL. Zope stops there and raises an error. Zope never looks in /Images because it has already found /Content/Images.

14.4.1.3. Readability¶

Context acquisition can make code more difficult to understand. A person reading your script can no longer simply look backwards up one containment hierarchy to see where an acquired object might be; many more places might be searched, all over the zope tree folder. And the order in which objects are searched, though it is consistent, can be confusing.

14.4.1.4. Fragility¶

Over-use of context acquisition can also lead to fragility. In object-oriented terms, context acquisition can lead to a site with low cohesion and tight coupling. This is generally regarded as a bad thing. More specifically, there are many simple actions by which an unwitting developer could break scripts that rely on context acquisition. These are more likely to occur than with container acquisition, because potentially every part of your site affects every other part, even in parallel folder branches.

For example, if you write a script that calls another script by a long and torturous path, you are assuming that the folder tree is not going to change. A maintenance decision to reorganize the folder hierarchy could require an audit of scripts in every part of the site to determine whether the reorganization will break anything.

Recall our Zoo example. There are several ways in which a zope maintainer could break the feed() script:

- Inserting another object with the name of the method

- This is a normal technique for customizing behavior in Zope, but context acquisition makes it more likely to happen by accident. Suppose that giraffe vaccination is controlled by a regularly scheduled script that calls Zoo/Vet/LargeAnimals/giraffe/feed. Suppose a content administrator doesn’t know about this script and adds a DTML page called vaccinate in the giraffe folder, containing information about vaccinating giraffes. This new vaccinate object will be acquired before Zoo/Vet/vaccinate. Hopefully you will notice the problem before your giraffes get sick.

- Calling an inappropriate path

- if you visit Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/buildings/visitor_reception/feed, will the reception area be filled with hippo food? One would hope not. This might even be possible for someone who has no permissions on the reception object. Such URLs are actually not difficult to construct. For example, using relative URLs in standard_html_header can lead to some quite long combinations of paths.

Thanks to Toby Dickenson for pointing out these fragility issues on the zope-dev mailing list.

14.5. Passing Parameters to Scripts¶

All scripts can be passed parameters. A parameter gives a script more information about what to do. When you call a script from the web, Zope will try to find the script’s parameters in the web request and pass them to your script. For example, if you have a script with parameters dolphin and REQUEST Zope will look for dolphin in the web request, and will pass the request itself as the REQUEST parameter. In practical terms this means that it is easy to do form processing in your script. For example, here is a form:

<form action="form_action">

Name of Hippo <input type="text" name="name" /><br />

Age of Hippo <input type="text" name="age" /><br />

<input type="submit" />

</form>

You can easily process this form with a script named form_action that includes name and age in its parameter list:

## Script (Python) "form_action"

##parameters=name, age

##

"Process form"

age=int(age)

message= 'This hippo is called %s and is %d years old' % (name, age)

if age < 18:

message += '\n %s is not old enough to drive!' % name

return message

There is no need to process the form manually to extract values from it. Form elements are passed as strings, or lists of strings in the case of checkboxes and multiple-select input.

In addition to form variables, you can specify any request variables as script parameters. For example, to get access to the request and response objects just include ‘REQUEST’ and ‘RESPONSE’ in your list of parameters. Request variables are detailed more fully in Appendix B: API Reference .

In the Script (Python) given above, there is a subtle problem. You are probably expecting an integer rather than a string for age, but all form variables are passed as strings. You could manually convert the string to an integer using the Python int built-in:

age = int(age)

But this manual conversion may be inconvenient. Zope provides a way for you to specify form input types in the form, rather than in the processing script. Instead of converting the age variable to an integer in the processing script, you can indicate that it is an integer in the form itself:

Age <input type="text" name="age:int" />

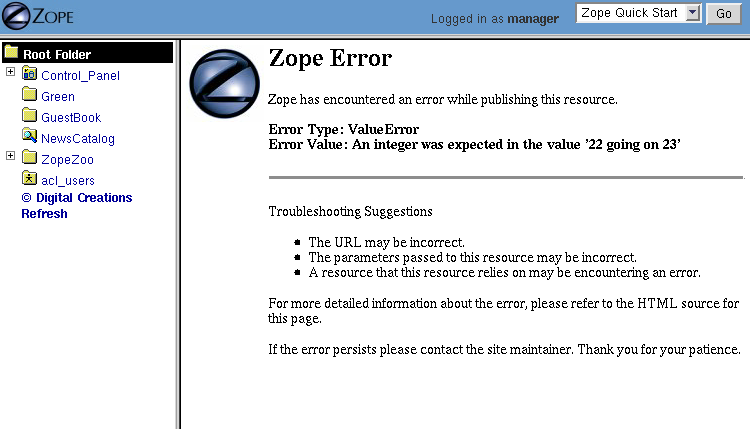

The ‘:int’ appended to the form input name tells Zope to automatically convert the form input to an integer. This process is called marshalling. If the user of your form types something that cannot be converted to an integer (such as “22 going on 23”) then Zope will raise an exception as shown in the figure below.

Parameter conversion error

It’s handy to have Zope catch conversion errors, but you may not like Zope’s error messages. You should avoid using Zope’s converters if you want to provide your own error messages.

Zope can perform many parameter conversions. Here is a list of Zope’s basic parameter converters.

- boolean

- Converts a variable to true or false. Variables that are 0, None, an empty string, or an empty sequence are false, all others are true.

- int

- Converts a variable to an integer.

- long

- Converts a variable to a long integer.

- float

- Converts a variable to a floating point number.

- string

- Converts a variable to a string. Most variables are strings already so this converter is seldom used.

- text

- Converts a variable to a string with normalized line breaks. Different browsers on various platforms encode line endings differently, so this script makes sure the line endings are consistent, regardless of how they were encoded by the browser.

- list

- Converts a variable to a Python list.

- tuple

- Converts a variable to a Python tuple. A tuple is like a list, but cannot be modified.

- tokens

- Converts a string to a list by breaking it on white spaces.

- lines

- Converts a string to a list by breaking it on new lines.

- date

- Converts a string to a DateTime object. The formats accepted are fairly flexible, for example ‘10/16/2000’, ‘12:01:13 pm’.

- required

- Raises an exception if the variable is not present.

- ignore_empty

- Excludes the variable from the request if the variable is an empty string.

These converters all work in more or less the same way to coerce a form variable, which is a string, into another specific type. You may recognize these converters from the chapter entitled Using Basic Zope Objects , in which we discussed properties. These converters are used by Zope’s property facility to convert properties to the right type.

The list and tuple converters can be used in combination with other converters. This allows you to apply additional converters to each element of the list or tuple. Consider this form:

<form action="processTimes">

<p>I would prefer not to be disturbed at the following

times:</p>

<input type="checkbox" name="disturb_times:list:date"

value="12:00 AM" /> Midnight<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="disturb_times:list:date"

value="01:00 AM" /> 1:00 AM<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="disturb_times:list:date"

value="02:00 AM" /> 2:00 AM<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="disturb_times:list:date"

value="03:00 AM" /> 3:00 AM<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="disturb_times:list:date"

value="04:00 AM" /> 4:00 AM<br />

<input type="submit" />

</form>

By using the list and date converters together, Zope will convert each selected time to a date and then combine all selected dates into a list named disturb_times.

A more complex type of form conversion is to convert a series of inputs into records. Records are structures that have attributes. Using records, you can combine a number of form inputs into one variable with attributes. The available record converters are:

- record

- Converts a variable to a record attribute.

- records

- Converts a variable to a record attribute in a list of records.

- default

- Provides a default value for a record attribute if the variable is empty.

- ignore_empty

- Skips a record attribute if the variable is empty.

Here are some examples of how these converters are used:

<form action="processPerson">

First Name <input type="text" name="person.fname:record" /><br />

Last Name <input type="text" name="person.lname:record" /><br />

Age <input type="text" name="person.age:record:int" /><br />

<input type="submit" />

</form>

This form will call the processPerson script with one parameter, person. The person variable will have the attributes fname, lname and age. Here’s an example of how you might use the person variable in your processPerson script:

## Script (Python) "processPerson"

##parameters=person

##

"Process a person record"

full_name="%s %s" % (person.fname, person.lname)

if person.age < 21:

return "Sorry, %s. You are not old enough to adopt an aardvark." % full_name

return "Thanks, %s. Your aardvark is on its way." % full_name

The records converter works like the record converter except that it produces a list of records, rather than just one. Here is an example form:

<form action="processPeople">

<p>Please, enter information about one or more of your next of

kin.</p>

<p>

First Name <input type="text" name="people.fname:records" />

Last Name <input type="text" name="people.lname:records" />

</p>

<p>

First Name <input type="text" name="people.fname:records" />

Last Name <input type="text" name="people.lname:records" />

</p>

<p>

First Name <input type="text" name="people.fname:records" />

Last Name <input type="text" name="people.lname:records" />

</p>

<input type="submit" />

</form>

This form will call the processPeople script with a variable called people that is a list of records. Each record will have fname and lname attributes. Note the difference between the records converter and the list:record converter: the former would create a list of records, whereas the latter would produce a single record whose attributes fname and lname would each be a list of values.

The order of combined modifiers does not matter; for example, int:list is identical to list:int.

Another useful parameter conversion uses form variables to rewrite the action of the form. This allows you to submit a form to different scripts depending on how the form is filled out. This is most useful in the case of a form with multiple submit buttons. Zope’s action converters are:

- action

- Appends the attribute value to the original form action of the form. This is mostly useful for the case in which you have multiple submit buttons on one form. Each button can be assigned to a script that gets called when that button is clicked to submit the form. A synonym for action is method.

- default_action

- Appends the attribute value to the original action of the form when no other action converter is used.

Here’s an example form that uses action converters:

<form action="employeeHandlers">

<p>Select one or more employees</p>

<input type="checkbox" name="employees:list" value="Larry" /> Larry<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="employees:list" value="Simon" /> Simon<br />

<input type="checkbox" name="employees:list" value="Rene" /> Rene<br />

<input type="submit" name="fireEmployees:action" value="Fire!" /><br />

<input type="submit" name="promoteEmployees:action" value="Promote!" />

</form>

We assume a folder ‘employeeHandlers’ containing two scripts named ‘fireEmployees’ and ‘promoteEmployees’. The form will call either the fireEmployees or the promoteEmployees script, depending on which of the two submit buttons is used. Notice also how it builds a list of employees with the list converter. Form converters can be very useful when designing Zope applications.

14.6. Script Security¶

All scripts that can be edited through the web are subject to Zope’s standard security policies. The only scripts that are not subject to these security restrictions are scripts that must be edited through the filesystem.

The chapter entitled Users and Security covers security in more detail. You should consult the Roles of Executable Objects and Proxy Roles sections for more information on how scripts are restricted by Zope security constraints.

14.6.1. Security Restrictions of Script (Python)¶

Scripts are restricted in order to limit their ability to do harm. What could be harmful? In general, scripts keep you from accessing private Zope objects, making unauthorized changes to Zope objects and accessing the server Zope is running on. These restrictions are implemented through a collection of limits on what your scripts can do. The limits are not effective enough to prevent malicious users from harming the Zope process on purpose. They only provide a safety belt against accidental bad code.

- Loop limits

Scripts cannot create infinite loops. If your script loops a very large number of times Zope will raise an error. This restriction covers all kinds of loops including for and while loops. The reason for this restriction is to limit your ability to hang Zope by creating an infinite loop.

This limit does not protect you from creating other sorts of infinite recursions and it’s still possible to hang the Zope process.

- Import limits

- Scripts cannot import arbitrary packages and modules. You are limited to importing the Products.PythonScripts.standard utility module, the AccessControl module, some helper modules (string, random, math, sequence), and modules which have been specifically made available to scripts by product authors. See Appendix B: API Reference for more information on these modules.

- Access limits

- You are restricted by standard Zope security policies when accessing objects. In other words the user executing the script is checked for authorization when accessing objects. As with all executable objects, you can modify the effective roles a user has when calling a script using Proxy Roles (see the chapter entitled Users and Security for more information). In addition, you cannot access objects whose names begin with an underscore, since Zope considers these objects to be private. Finally, you can define classes in scripts but it is not really practical to do so, because you are not allowed to access attributes of these classes! Even if you were allowed to do so, the restriction against using objects whose names begin with an underscore would prevent you from using your class’s __init__ method. If you need to define classes, use packages You may, however, define functions in scripts, although it is rarely useful or necessary to do so. In practice, a Script in Zope is treated as if it were a single method of the object you wish to call it on.

- Writing limits

- In general you cannot directly change Zope object attributes using scripts. You should call the appropriate methods from the Zope API instead.

Despite these limits, a determined user could use large amounts of CPU time and memory using Python-based Scripts. So malicious scripts could constitute a kind of denial of service attack by using lots of resources. These are difficult problems to solve. You probably should not grant access to scripts to untrusted people.

14.7. Python versus Page Templates¶

Zope gives you multiple ways to script. For small scripting tasks the choice of Python-based Scripts or Page Templates probably doesn’t make a big difference. For larger, logic-oriented tasks you should use Python-based Scripts or write packages on the file-system.

For presentation, Python should not be used; instead you use ZPT.

Just for the sake of comparison, here is a simple presentational script suggested by Gisle Aas in ZPT and Python.

In ZPT:

<div tal:repeat="item context/objectValues"

tal:replace="python:'%s: %s\n' % (item.getId(), str(item))" />

In Python:

for item in context.objectValues():

print "%s: %s" % (item.getId(), item)

print "done"

return printed

14.8. Remote Scripting and Network Services¶

Web servers are used to serve content to software clients; usually people using web browser software. The software client can also be another computer that is using your web server to access some kind of service.

Because Zope exposes objects and scripts on the web, it can be used to provide a powerful, well organized, secure web API to other remote network application clients.

There are two common ways to remotely script Zope. The first way is using a simple remote procedure call protocol called XML-RPC. XML-RPC is used to execute a procedure on a remote machine and get a result on the local machine. XML-RPC is designed to be language neutral, and in this chapter you’ll see examples in Python and Java.

The second common way to remotely script Zope is with any HTTP client that can be automated with a script. Many language libraries come with simple scriptable HTTP clients and there are many programs that let you you script HTTP from the command line.

14.8.1. Using XML-RPC¶

XML-RPC is a simple remote procedure call mechanism that works over HTTP and uses XML to encode information. XML-RPC clients have been implemented for many languages including Python, Java and JavaScript.

In-depth information on XML-RPC can be found at the “XML-RPC website”:http://www.xmlrpc.com/.

All Zope scripts that can be called from URLs can be called via XML-RPC. Basically XML-RPC provides a system to marshal arguments to scripts that can be called from the web. As you saw earlier in the chapter Zope provides its own marshaling controls that you can use from HTTP. XML-RPC and Zope’s own marshaling accomplish much the same thing. The advantage of XML-RPC marshaling is that it is a reasonably supported standard that also supports marshaling of return values as well as argument values.

Here’s a fanciful example that shows you how to remotely script a mass firing of janitors using XML-RPC.

Here’s the code in Python:

import xmlrpclib

server = xmlrpclib.Server('http://www.zopezoo.org/')

for employee in server.JanitorialDepartment.personnel():

server.fireEmployee(employee)

In Java:

try {

XmlRpcClient server = new XmlRpcClient("http://www.zopezoo.org/");

Vector employees = (Vector) server.execute("JanitorialDepartment.personnel");

int num = employees.size();

for (int i = 0; i < num; i++) {

Vector args = new Vector(employees.subList(i, i+1));

server.execute("fireEmployee", args);

}

} catch (XmlRpcException ex) {

ex.printStackTrace();

} catch (IOException ioex) {

ioex.printStackTrace();

}

Actually the above example will probably not run correctly, since you will most likely want to protect the fireEmployee script. This brings up the issue of security with XML-RPC. XML-RPC does not have any security provisions of its own; however, since it runs over HTTP it can leverage existing HTTP security controls. In fact Zope treats an XML-RPC request exactly like a normal HTTP request with respect to security controls. This means that you must provide authentication in your XML-RPC request for Zope to grant you access to protected scripts.

14.8.2. Remote Scripting with HTTP¶

Any HTTP client can be used for remotely scripting Zope.

On Unix systems you have a number of tools at your disposal for remotely scripting Zope. One simple example is to use wget to call Zope script URLs and use cron to schedule the script calls. For example, suppose you have a Zope script that feeds the lions and you would like to call it every morning. You can use wget to call the script like so:

$ wget --spider http://www.zopezope.org/Lions/feed

The spider option tells wget not to save the response as a file. Suppose that your script is protected and requires authorization. You can pass your user name and password with wget to access protected scripts:

$ wget --spider --http-user=ZooKeeper \

--http-passwd=SecretPhrase \

http://www.zopezope.org/Lions/feed

Now let’s use cron to call this command every morning at 8am. Edit your crontab file with the crontab command:

$ crontab -e

Then add a line to call wget every day at 8 am:

0 8 * * * wget -nv --spider --http_user=ZooKeeper \

--http_pass=SecretPhrase http://www.zopezoo.org/Lions/feed

(Beware of the linebreak – the above should be input as one line, minus the backslash).

The only difference between using cron and calling wget manually is that you should use the nv switch when using cron since you don’t care about output of the wget command.

For our final example let’s get really perverse. Since networking is built into so many different systems, it’s easy to find an unlikely candidate to script Zope. If you had an Internet-enabled toaster you would probably be able to script Zope with it. Let’s take Microsoft Word as our example Zope client. All that’s necessary is to get Word to agree to tickle a URL.

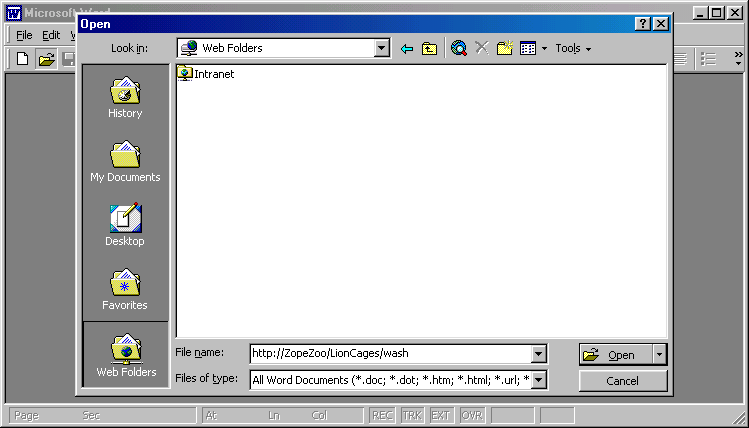

The easiest way to script Zope with Word is to tell word to open a document and then type a Zope script URL as the file name as shown in [8-9].

Calling a URL with Microsoft Word

Word will then load the URL and return the results of calling the Zope script. Despite the fact that Word doesn’t let you POST arguments this way, you can pass GET arguments by entering them as part of the URL.

You can even control this behavior using Word’s built-in Visual Basic scripting. For example, here’s a fragment of Visual Basic that tells Word to open a new document using a Zope script URL:

Documents.Open FileName:="http://www.zopezoo.org/LionCages/wash?use_soap=1&water_temp=hot"

You could use Visual Basic to call Zope script URLs in many different ways.

Zope’s URL to script call translation is the key to remote scripting. Since you can control Zope so easily with simple URLs you can easy script Zope with almost any network-aware system.

14.9. Conclusion¶

With scripts you can control Zope objects and glue together your application’s logic, data, and presentation. You can programmatically manage objects in your Zope folder hierarchy by using the Zope API.