9. Basic Zope Scripting¶

So far, you’ve learned about some basic Zope objects and how to manage them through the Zope Management Interface. This chapter shows you how to manage Zope objects programmatically.

9.1. Calling Methods From the Web¶

Since Zope is a web application server, the easiest way to communicate with Zope is through a web browser. Any URL your browser requests from the server is mapped to both an object and a method. The method is executed on the object, and a response is sent to your browser.

As you might already know, visiting the URL

http://localhost:8080/

returns the Zope Quick Start page. In this case, we only specify an object – the root object – but no method. This just works because there is a default method defined for Folders: index_html. Visiting the URL:

http://localhost:8080/index_html

returns (almost) exactly the same page.

You can also specify the root object as:

http://localhost:8080/manage_main

but in this case the manage_main method is called, and the workspace frame displays the root content of your Zope site, without the navigator frame.

The same method can be called on other objects: when you visit the URL:

http://localhost:8080/Control_Panel/manage_main

the manage_main method is called on the Control Panel object.

Sometimes a query string is added to the URL, e.g.:

http://localhost:8080/manage_main?skey=meta_type

The query string is used for passing arguments to the method. In this case, the argument skey specifies the sort key with the value meta_type. Based on this argument, the manage_main method returns a modified version of the basic page: the sub-objects are sorted by Type, not by Name as they are without that query string.

While the manage_main method is defined in the class of the object, index_html is (by default) a DTML Method object in the root folder that can be modified through the web. index_html itself is a presentation object, but when called on a folder, it behaves as a method that returns the default view of the folder.

9.1.1. Method Objects and Context Objects¶

When you call a method, you usually want to single out some object that is central to the method’s task, either because that object provides information that the method needs, or because the method will modify that object. In object-oriented terms, we want to call the method on this particular object. But in conventional object-oriented programming, each object can perform the methods that are defined in (or inherited by) its class. How is it that one Zope object can be used as a method for (potentially) many other objects, without its being defined by the classes that define these objects?

Recall that in the chapter entitled Acquisition, we learned that Zope can find objects in different places by acquiring them from parent containers. Acquisition allows us to treat an object as a method that can be called in the context of any suitable object, just by constructing an appropriate URL. The object on which we call a method gives it a context in which to execute. Or, to put it another way: the context is the environment in which the method executes, from which the method may get information that it needs in order to do its job.

Another way to understand the context of a method is to think of the method as a function in a procedural programming language, and its context as an implicit argument to that function.

While the Zope way to call methods in the context of objects works differently than the normal object-oriented way to call class-defined methods on objects, they are used the same way, and it is simpler to say that you are calling the method on the object.

There are two general ways to call methods on objects: by visiting an URL, and by calling the method from another method.

9.1.2. URL Traversal and Acquisition¶

The concept of calling methods in the context of objects is a powerful feature that enables you to apply logic to objects, like documents or folders, without having to embed any actual code within the object.

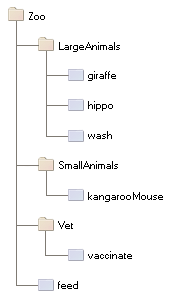

For example, suppose you have a collection of objects and methods, as shown in the figure below.

A collection of objects and methods

To call the feed method on the hippo object, you would visit the URL:

Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/feed

To call the feed method on the kangarooMouse object you would visit the URL:

Zoo/SmallAnimals/kangarooMouse/feed

These URLs place the feed method in the context of the hippo and kangarooMouse objects, respectively.

Zope breaks apart the URL and compares it to the object hierarchy, working backwards until it finds a match for each part. This process is called URL traversal. For example, when you give Zope the URL:

Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/feed

it starts at the root folder and looks for an object named Zoo. It then moves to the Zoo folder and looks for an object named LargeAnimals. It moves to the LargeAnimals folder and looks for an object named hippo. It moves to the hippo object and looks for an object named feed. The feed method cannot be found in the hippo object and is located in the Zoo folder by using acquisition. Zope always starts looking for an object in the last object it traversed, in this case: hippo. Since hippo does not contain anything, Zope backs up to hippo’s immediate container LargeAnimals. The feed method is not there, so Zope backs up to LargeAnimals container, Zoo, where feed is finally found.

Now Zope has reached the end of the URL and has matched objects to every name in the URL. Zope recognizes that the last object found, feed, is callable, and calls it in the context of the second-to-last object found: the hippo object. This is how the feed method is called on the hippo object.

Likewise, you can call the wash method on the hippo by visiting the URL:

Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/wash

In this case, Zope acquires the wash method from the LargeAnimals folder.

Note that Script (Python) and Page Template objects are always method objects. You can’t call another method in the context of one of them. Given wash is such a method object, visiting the URL

Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/wash/feed

would also call the wash method on the hippo object. Instead of traversing to feed, everything after the method wash is cut off of the URL and stored in the variable traverse_subpath.

9.1.3. The Special Folder Object index_html¶

As already mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, Zope uses the default method if no other method is specified. The default method for Folders is index_html, which does not necessarily need to be a method itself. If it isn’t a callable, the default method of the object index_html is called on index_html. This is analogous to how an index.html file provides a default view for a directory in Apache and other web servers. Instead of explicitly including the name index_html in your URL to show default content for a Folder, you can omit it and still gain the same effect.

For example, if you create an index_html object in your Zoo Folder, and view the folder by clicking the View tab or by visiting the URL:

http://localhost:8080/Zoo/

Zope will call the index_html object in the Zoo folder and display its results. You could instead use the more explicit URL:

http://localhost:8080/Zoo/index_html

and it will display the same content.

A Folder can also acquire an index_html object from its parent Folders. You can use this behavior to create a default view for a set of Folders. To do so, create an index_html object in a Folder that contains another set of Folders. This default view will be used for all the Folders in the set. This behavior is already evident in Zope: if you create a set of empty Folders in the Zope root Folder, you may notice that when you view any of the Folders via a URL, the content of the “root” Folder’s index_html method is displayed. The index_html in the root Folder is acquired. Furthermore, if you create more empty Folders inside the Folders you’ve just created in the root Folder, a visit to these Folders’ URLs will also display the root Folder’s index_html. This is acquisition at work.

If you want a different default view of a given Folder, just create a custom index_html object in that particular Folder. This allows you to override the default view of a particular Folder on a case-by-case basis, while allowing other Folders defined at the same level to acquire a common default view.

The index_html object may be a Page Template, a Script (Python) object, a DTML Method or any other Zope object that is URL-accessible and that returns browser-renderable content. The content is typically HTML, but Zope doesn’t care. You can return XML, or text, or anything you like.

9.2. Using Python-based Scripts¶

Now let us take a look at a basic method object: Script (Python).

9.2.1. The Python Language¶

Python is a high-level, object oriented scripting language. Most of Zope is written in Python. Many folks like Python because of its clarity, simplicity, and ability to scale to large projects.

There are many resources available for learning Python. The python.org website has lots of Python documentation including a tutorial by Python’s creator, Guido van Rossum.

For people who have already some programming experience, Dive Into Python is a great online resource to learn python.

Python comes with a rich set of modules and packages. You can find out more about the Python standard library at the python.org website.

9.2.2. Creating Python-based Scripts¶

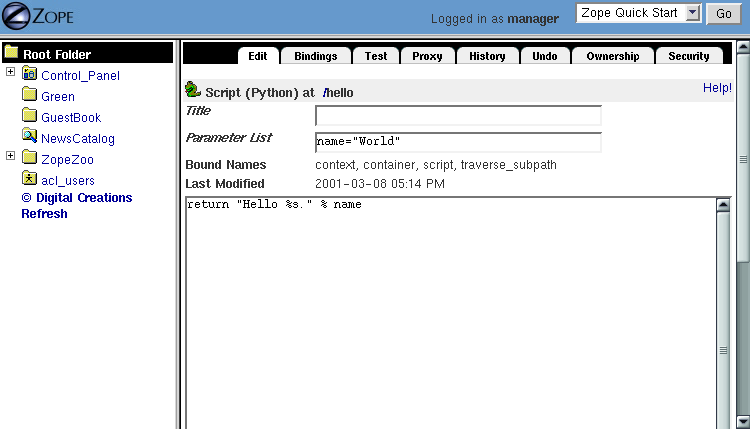

To create a Python-based Script, select Script (Python) from the Add drop-down list. Name the script hello, and click the Add and Edit button. You should now see the Edit view of your script.

This screen allows you to control the parameters and body of your script. You can enter your script’s parameters in the parameter list field. Type the body of your script in the text area at the bottom of the screen.

Enter:

name="World"

into the parameter list field, and in the body of the script, type:

return "Hello %s." % name

Our script is now equivalent to the following function definition in standard Python syntax:

def hello(name="World"):

return "Hello %s." % name

The script should return a result similar to the following image:

Script editing view

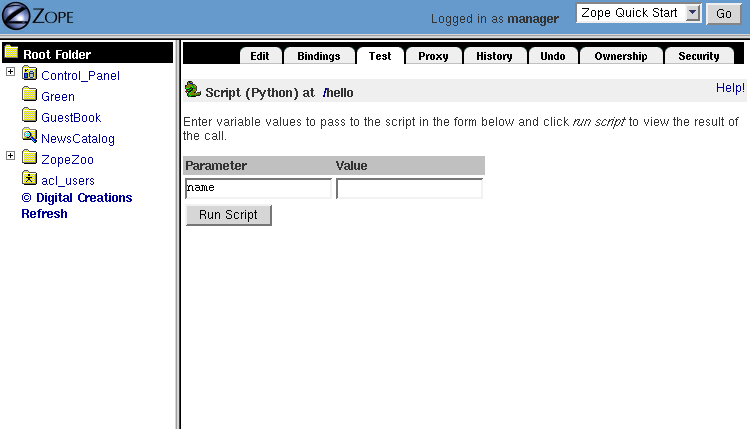

You can now test the script by going to the Test tab, as shown in the following figure.

Testing a script

Leave the name field blank, and click the Run Script button. Zope should return “Hello World.” Now go back and try entering your name in the Value field, and clicking the Run Script button. Zope should now say “hello” to you.

Since scripts are called on Zope objects, you can get access to Zope objects via the context variable. For example, this script returns the number of objects contained by a given Zope object:

## Script (Python) "numberOfObjects"

##

return len( context.objectIds() )

Note that the lines at the top starting with a double hash (##) are generated by Zope when you view the script outside the Edit tab of the ZMI, e.g., by clicking the view or download link at the bottom of the Edit tab. We’ll use this format for our examples.

The script calls context.objectIds(), a method in the Zope API, to get a list of the contained objects. objectIds is a method of Folders, so the context object should be a Folder-like object. The script then calls len() to find the number of items in that list. When you call this script on a given Zope object, the context variable is bound to the context object. So, if you called this script by visiting the URL:

FolderA/FolderB/numberOfObjects

the context parameter would refer to the FolderB object.

When writing your logic in Python, you’ll typically want to query Zope objects, call other scripts, and return reports. Suppose you want to implement a simple workflow system, in which various Zope objects are tagged with properties that indicate their status. You might want to produce reports that summarize which objects are in which state. You can use Python to query objects and test their properties. For example, here is a script named objectsForStatus with one parameter, ‘status’:

## Script (Python) "objectsForStatus"

##parameters=status

##

""" Returns all sub-objects that have a given status property.

"""

results=[]

for object in context.objectValues():

if object.getProperty('status') == status:

results.append(object)

return results

This script loops through an object’s sub-objects, and returns all the sub-objects that have a:

status

property with a given value.

9.2.3. Accessing the HTTP Request¶

What if we need to get user input, e.g., values from a form? We can find the REQUEST object, which represents a Zope web request, in the context. For example, if we visited our feed script via the URL:

Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo/feed?food_type=spam

we could access the food_type variable as:

context.REQUEST.food_type

This same technique works with variables passed from forms.

Another way to get the REQUEST is to pass it as a parameter to the script. If REQUEST is one of the script’s parameters, Zope will automatically pass the HTTP request and assign it to this parameter. We could then access the food_type variable as:

REQUEST.food_type

9.2.4. String Processing in Python¶

One common use for scripts is to do string processing. Python has a number of standard modules for string processing. Due to security restrictions, you cannot do regular expression processing within Python-based Scripts. If you really need regular expressions, you can easily use them in External Methods, described in a subsequent chapter. However, in a Script (Python) object, you do have access to string methods.

Suppose you want to change all the occurrences of a given word in a text file. Here is a script, replaceWord, that accepts two arguments: word and replacement. This will change all the occurrences of a given word in a File:

## Script (Python) "replaceWord"

##parameters=word, replacement

##

""" Replaces all the occurrences of a word with a replacement word in

the source text of a text file. Call this script on a text file to use

it.

Note: you will need permission to edit the file in order to call this

script on the *File* object. This script assumes that the context is

a *File* object, which provides 'data', 'title', 'content_type' and

the manage_edit() method.

"""

text = context.data

text = text.replace(word, replacement)

context.manage_edit(context.title, context.content_type, filedata=text)

You can call this script from the web on a text File in order to change the text. For example, the URL:

Swamp/replaceWord?word=Alligator&replacement=Crocodile

would call the replaceWord script on the text File named:

Swamp

and would replace all occurrences of the word:

Alligator

with:

Crocodile

See the Python documentation for more information about manipulating strings from Python.

One thing that you might be tempted to do with scripts is to use Python to search for objects that contain a given word within their text or as a property. You can do this, but Zope has a much better facility for this kind of work: the Catalog. See the chapter entitled Searching and Categorizing Content for more information on searching with Catalogs.

9.2.5. Print Statement Support¶

Python-based Scripts have a special facility to help you print information. Normally, printed data is sent to standard output and is displayed on the console. This is not practical for a server application like Zope, since the service does not always have access to the server’s console. Scripts allow you to use print anyway, and to retrieve what you printed with the special variable printed. For example:

## Script (Python) "printExample"

##

for word in ('Zope', 'on', 'a', 'rope'):

print word

return printed

This script will return:

Zope

on

a

rope

The reason that there is a line break in between each word is that Python adds a new line after every string that is printed.

You might want to use the print statement to perform simple debugging in your scripts. For more complex output control, you probably should manage things yourself by accumulating data, modifying it, and returning it manually, rather than relying on the print statement. And for controlling presentation, you should return the script output to a Page Template or DTML page, which then displays the return value appropriately.

9.2.6. Built-in Functions¶

Python-based Scripts give you a slightly different menu of built-ins than you’d find in normal Python. Most of the changes are designed to keep you from performing unsafe actions. For example, the open function is not available, which keeps you from being able to access the file system. To partially make up for some missing built-ins, a few extra functions are available.

The following restricted built-ins work the same as standard Python built-ins: None, abs, apply, callable, chr, cmp, complex, delattr, divmod, filter, float, getattr, hash, hex, int, isinstance, issubclass, list, len, long, map, max, min, oct, ord, repr, round, setattr, str, and tuple. For more information on what these built-ins do, see the online Python Documentation.

The range and pow functions are available and work the same way they do in standard Python; however, they are limited to keep them from generating very large numbers and sequences. This limitation helps to avoid accidental long execution times.

In addition, these DTML utility functions are available: DateTime and test. See Appendix A, DTML Reference for more information on these functions.

Finally, to make up for the lack of a type function, there is a same_type function that compares the type of two or more objects, returning true if they are of the same type. So, instead of saying:

if type(foo) == type([]):

return "foo is a list"

... to check if foo is a list, you would instead use the same_type function:

if same_type(foo, []):

return "foo is a list"

9.3. Calling ZPT from Scripts¶

Often, you would want to call a Page Template from a Script. For instance, a common pattern is to call a Script from an HTML form. The Script would process user input, and return an output page with feedback messages - telling the user her request executed correctly, or signalling an error as appropriate.

Scripts are good at logic and general computational tasks but ill-suited for generating HTML. Therefore, it makes sense to delegate the user feedback output to a Page Template and call it from the Script. Assume we have this Page Template with the id ‘hello_world_pt’:

<p>Hello <span tal:replace="options/name | default">World</span>!</p>

You will learn more about Page Templates in the next chapter. For now, just understand that this Page Template generates an HTML page based on the value name. Calling this template from a Script and returning the result could be done with the following line:

return context.hello_world_pt(name="John Doe")

The name parameter to the Page Template ends up in the:

options/name

path expression. So the returned HTML will be:

<p>Hello John Doe!</p>

Note that:

context.hello_world_pt

works because there is no dot in the id of the template. In Python, dots are used to separate ids. This is the reason why Zope often uses ids like index_html instead of the more common index.html and why this example uses hello_world_pt instead of hello_world.pt.

However, if desired, you can use dots within object ids. Using getattr to access the dotted id, the modified line would look like this:

return getattr(context, 'hello_world.pt')(name="John Doe")

9.4. Returning Values from Scripts¶

Scripts have their own variable scope. In this respect, scripts in Zope behave just like functions, procedures, or methods in most programming languages. If you name a script updateInfo, for example, and updateInfo assigns a value to a variable status, then status is local to your script: it gets cleared once the script returns. To get at the value of a script variable, we must pass it back to the caller with a return statement.

Scripts can only return a single object. If you need to return more than one value, put them in a dictionary and pass that back.

Suppose you have a Python script compute_diets, out of which you want to get values:

## Script (Python) "compute_diets"

d = {'fat': 10,

'protein': 20,

'carbohydrate': 40,

}

return d

The values would, of course, be calculated in a real application; in this simple example, we’ve simply hard-coded some numbers.

You could call this script from ZPT like this:

<p tal:repeat="diet context/compute_diets">

This animal needs

<span tal:replace="diet/fat" />kg fat,

<span tal:replace="diet/protein" />kg protein, and

<span tal:replace="diet/carbohydrate" />kg carbohydrates.

</p>

More on ZPT in the next chapter.

9.5. The Zope API¶

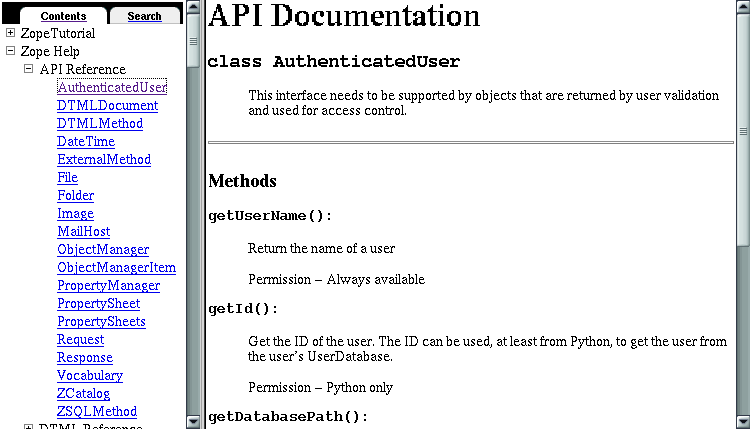

One of the main reasons to script in Zope is to get convenient access to the Zope Application Programmer Interface (API). The Zope API describes built-in actions that can be called on Zope objects. You can examine the Zope API in the help system, as shown in the figure below.

Zope API Documentation

Suppose you would like a script that takes a file you upload from a form, and creates a Zope File object in a Folder. To do this, you’d need to know a number of Zope API actions. It’s easy enough to read files in Python, but once you have the file, you must know which actions to call in order to create a new File object in a Folder.

There are many other things that you might like to script using the Zope API: any management task that you can perform through the web can be scripted using the Zope API, including creating, modifying, and deleting Zope objects. You can even perform maintenance tasks, like restarting Zope and packing the Zope database.

The Zope API is documented in Appendix B, API Reference, as well as in the Zope online help. The API documentation shows you which classes inherit from which other classes. For example, Folder inherits from ObjectManager, which means that Folder objects have all the methods listed in the ObjectManager section of the API reference.

To get you started and whet your appetite, we will go through some example Python scripts that demonstrate how you can use the Zope API:

9.5.1. Get all objects in a Folder¶

The objectValues() method returns a list of objects contained in a Folder. If the context happens not to be a Folder, nothing is returned:

objs = context.objectValues()

9.5.2. Get the id of an object¶

The id is the “handle” to access an object, and is set at object creation:

id = context.getId()

Note that there is no setId() method: you have to either use the ZMI to rename them, set their id attribute via security-unrestricted code, or use the `` manage_renameObject`` or manage_renameObjects API methods exposed upon the container of the object you want to rename.

9.5.3. Get the Zope root Folder¶

The root Folder is the top level element in the Zope object database:

root = context.getPhysicalRoot()

9.5.4. Get the physical path to an object¶

The getPhysicalPath() method returns a list containing the ids of the object’s containment hierarchy:

path_list = context.getPhysicalPath()

path_string = "/".join(path_list)

9.5.5. Get an object by path¶

restrictedTraverse() is the complement to getPhysicalPath().

The path can be absolute – starting at the Zope root – or relative to the context:

path = "/Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo"

hippo_obj = context.restrictedTraverse(path)

9.5.6. Get a property¶

getProperty()

returns a property of an object. Many objects support properties (those that are derived from the PropertyManager class), the most notable exception being DTML Methods, which do not:

pattern = context.getProperty('pattern')

return pattern

9.5.7. Change properties of an object¶

The object has to support properties, and the property must exist:

values = {'pattern' : 'spotted'}

context.manage_changeProperties(values)

9.5.8. Traverse to an object and add a new property¶

We get an object by its absolute path, add a property weight and set it to some value. Again, the object must support properties in order for this to work:

path = "/Zoo/LargeAnimals/hippo"

hippo_obj = context.restrictedTraverse(path)

hippo_obj.manage_addProperty('weight', 500, 'int')